If you work in Brussels, Geneva or New York there’s a good chance you have been to or spoken at events where there are interpreters.

I regularly work with interpreters in Brussels and one of the things that bond us is the often appalling standard of public speaking in this town (particularly in the EU institutions).

Contrary to popular belief, interpreters aren’t actually photocopiers: a speaker can’t put in zero effort, push a button and then expect Abraham Lincoln to emerge on the other side. And with more and more panels, conferences and public events being clipped and put on YouTube, Twitter etc, how someone comes across orally is hugely important for their own and their organisation’s reputation.

But an interpreter is only as good as the raw materials they are given to work with, not least because there are strict rules about not deviating too far from how the speaker they are working from actually speaks. And if that speaker would be beaten hands down in an oratory competition by a sack of wet cement then, well, you can imagine the rest….

The first thing for speakers to get to grips with is that interpreting is one of the most cognitively demanding things a human being can do. And that’s before you even get to whether or not they are interpreting a sub-optimal speaker.

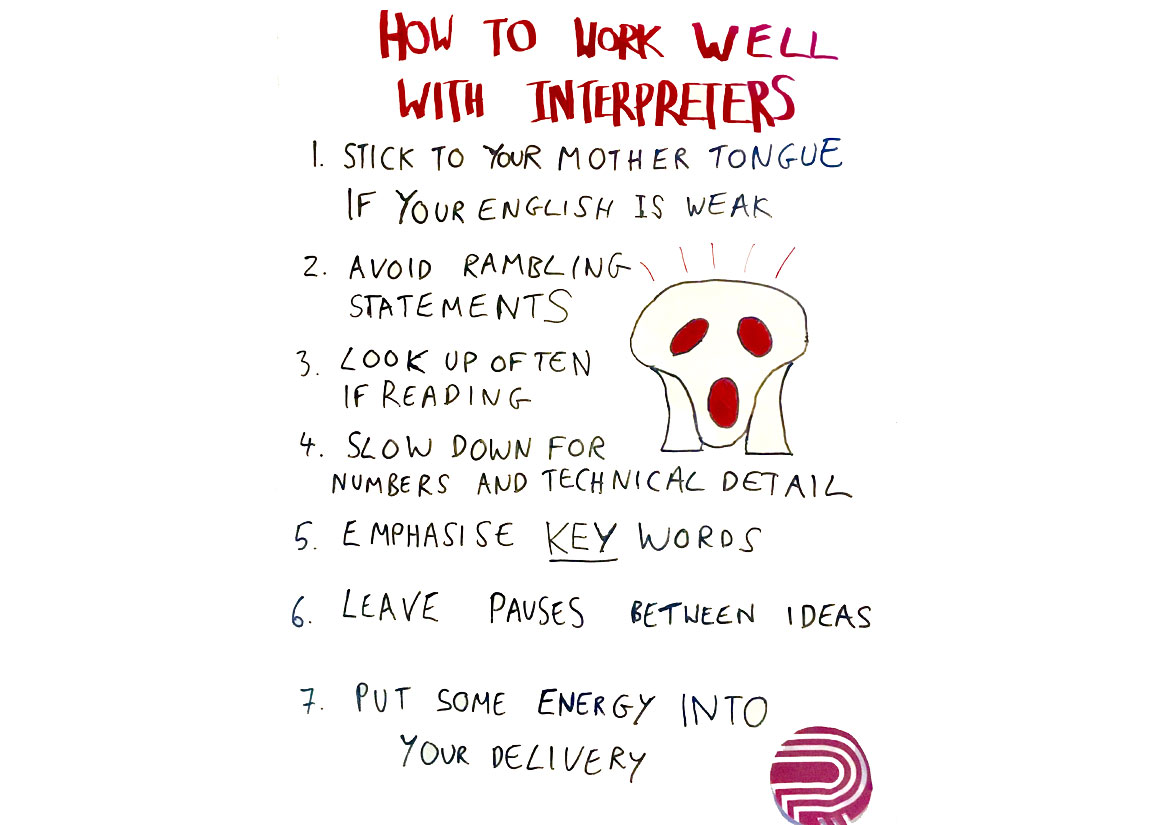

So here are a few tips on how to get the best out of interpreters, so that they can do their job…and help each speaker make as positive an impact as possible. This list is not exhaustive and as soon as I’d posted the original image on LinkedIn several other thoughts came to mind including making eye contact with the audience and no egregious use of native language idioms. Someone on LinkedIn also suggested submitting an advance copy of speeches to the interpreters and, where this is possible, I think it’s a great idea.

None of these pointers are rocket science. But speakers who incorporate them into their speeches and statements will come across much better than those who simply push the button and are surprised when they get the response ‘computer says NO’.

(Incidentally, the reason I’ve used English in the first example is that interpreters rarely complain about native English speakers trying to speak other languages and doing it badly (mostly because they don’t make the effort). But the same tips would apply.)