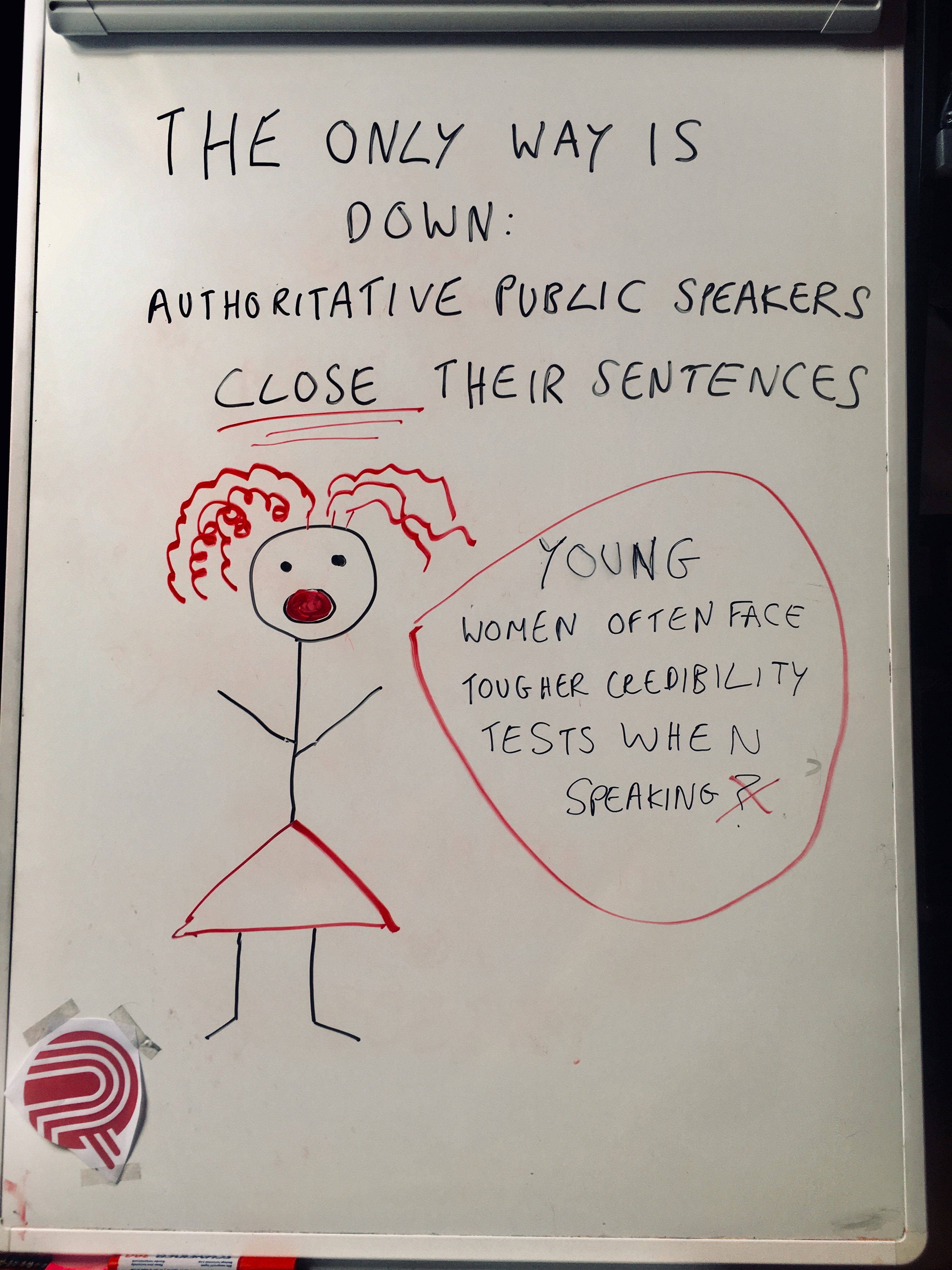

We can take it as gospel that everyone wants to come across as authoritative when speaking in public.

But a recurring feature of my presentation and media training sessions involving young women (anyone under 30 in my world) is that their peers often end up saying their real life and practise performances don’t do them justice and lack credibility.

Of course, this can happen to men too but there’s a specific lack of authority perception that seems to attach itself stubbornly to younger women’s performances. It’s not a question of knowledge or talent: it’s purely the public delivery element that lets many of them down.

However, I’ve recently cracked part of what I think is behind this and thankfully it’s relatively easy to correct.

Consider the following statements by reading them aloud to yourself:

- We think that it’s really important for more NGOs to talk to EU governments earlier on in the process.

- We think that it’s really important for more NGOs to talk to EU governments earlier on in the process?

Which one is more authoritative? Hopefully, you’ve picked the first option…

The reason for this is that one of the ways in which relatively junior or under-confident speakers try to compensate for their insecurity is to constantly ‘check in’ to make sure that their audience is following what they are saying. This usually takes the form of the speaker inflecting their voice so that it goes up at the end of sentences and sounds like a question.

This is clearly a non-verbal way of asking the audience/interlocutor if they have understood and are following what the speaker is saying so far.

Unfortunately, it can also create the impression of uncertainty because the sentences remain open-ended rather than declaratory. As a result, the speaker can seem less across her material than she really is because her hesitant tone makes her sound as though she is questioning herself.

A parallel experience for me would be when I speak French in Brussels. A lot of the time, people switch to English because I often sound under-confident (i.e. the tone of my voice appears to be questioning my grasp of French grammar) even when it later turns out that have been speaking correctly and am not causing people’s ears to bleed whenever I open my mouth.

This means that if you want to be authoritative, it’s probably better to be firm with colleagues (or yourself) about closing the ends of sentences and, if necessary, taking deliberate breaks when speaking to ask if the audience has followed everything you’ve said.

In a nutshell, if you want to be taken seriously then your voice and grasp of subject need to be working in tandem during public speaking. Otherwise, it doesn’t matter if you are the expert in your field. A hesitant or uncertain delivery can lead an audience to form unfavourable snap judgments, which, as we know can often be stubbornly difficult to shift.

Did you like the blog?

If yes, why not sign up to receive it automatically at the top of the page?