These are weird times and strange things are happening – like politicians shutting up and listening. In France, President Macron has been seen listening during the National Debates he set up to soothe public anger over his handling of the country which triggered the Gilets Jaunes protests. In the UK, Labour’s Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell has said the socialists need to undertake a ‘massive listening exercise’ after eight MPs quit the party over its handling of Brexit and antisemitism. Similar exercises are being pondered by politicians across Europe.

Cynics sneer that such events are just PR stunts. Others are starting to ask why it’s taken so long to make it happen. Whatever your view, when handled properly, listening exercises have proved capable of involving the public in a way that not only informs but actively brings people together even on intensely contentious issues. Just ask those who took part in Ireland’s Citizens’ Assemblies ahead of last year’s abortion referendum. The rules are pretty simple: those on both sides of the debate must listen to the views of others and think through their position in a neutral, structured and non-shouty environment. No knee-jerks allowed.

You don’t have to be a genius to realise there should have been a political listening exercise in the UK in 2016. And it’s interesting that two Labour MPs, Lisa Nandy and Stella Creasy are now pushing hard for Citizens’ Assemblies to end the Brexit impasse. This is an excellent initiative. As someone who is personally and politically horrified by what’s going on in the UK, I can honestly say I am less worried about Brexit than I am about people being unable to listen and talk about things they disagree over.

Listening properly is an enlightened art form. In Buddhism, the Buddha is described as ‘the one who observes the sounds of the world’. However, as Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman point out in Harvard Business Review’s e-book on workplace empathy, most people don’t really listen, they just wait to talk.

Bad listening translates into bad communication because bad listeners often don’t listen to how badly they themselves come across either. And it’s not just in politics.

Whether it’s some weird passive aggressive standoff between NGOs and industry representatives on panels in Brussels, or my father telling another driver that ‘he’s been very foolish’ in a minor roadside altercation, everywhere I look poor listening and weak communication contribute to misunderstandings, further polarisation and the enlargement of the vicious circle.

So, what can we do to listen better to ourselves and others?

Naturally, I am not referring to you, dear reader. I am quite sure that your listening skills are perfect and that you are a natural empath. But if you have friends, clients or colleagues who could sharpen up their internal and external listening skills you might want to draw their attention to the following points.

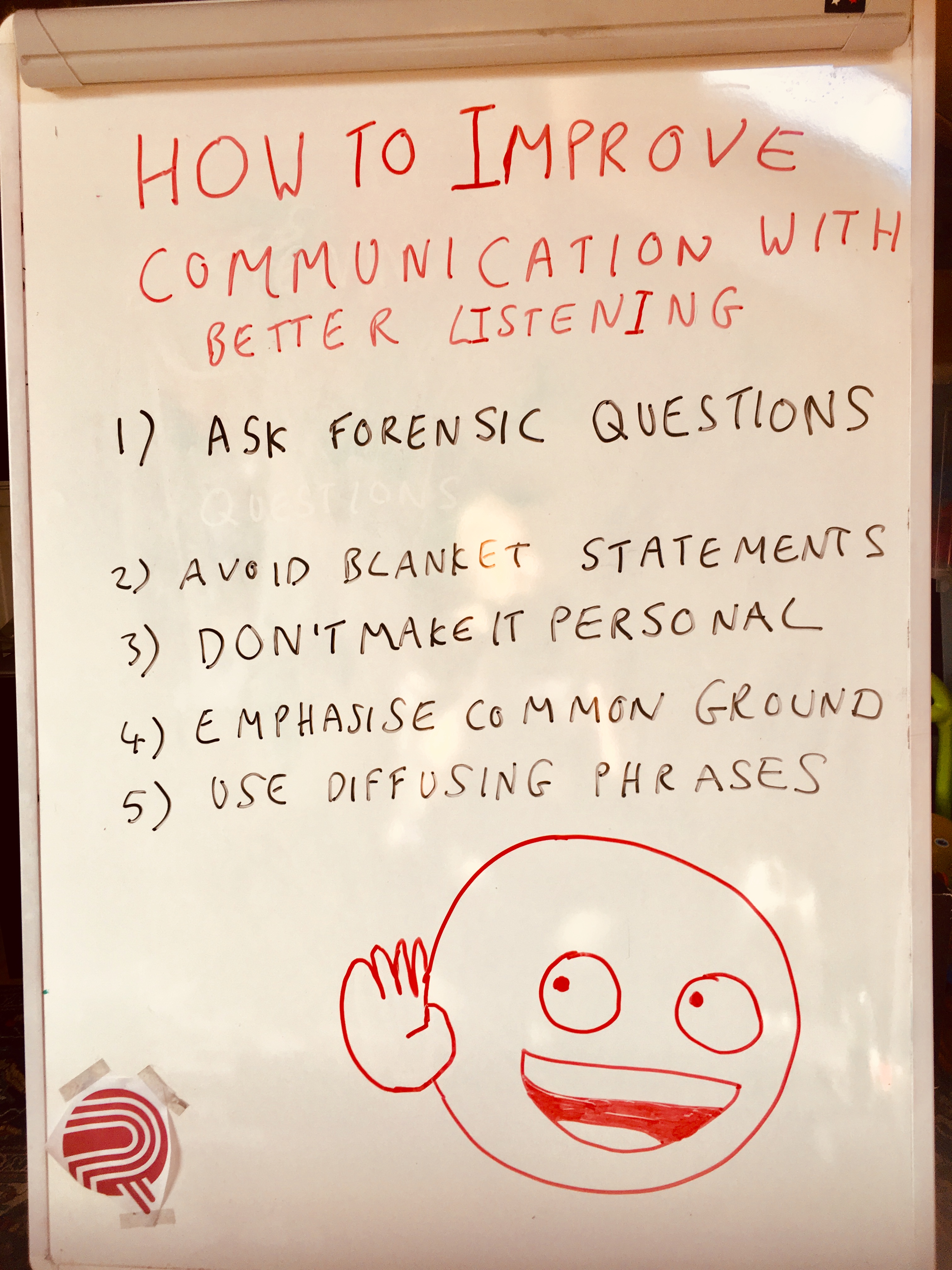

1. Be forensic

Ask lots of questions as opposed to grandstanding and attacking (yes, MEPs I’m talking to you). If you disagree or are appalled by someone’s view, ask them lots of short, simple questions that challenge their thinking and force them to explain it. It will improve your listening skills and give you an insight into how they think. Chances are you may challenge some of their underlying deliberative processes as well.

2. Blanket statements often alienate people

Much of the time people present their opinion as the definitive view. For example, ‘Industry is not pulling its weight on climate change’ is a snappy soundbite but it will irritate those who hold different views because it’s absolutist. Softening it by saying ‘I think’ or ‘Our view is’…can go some way to lessening the sting and shows that you are generally capable of exchanging views, not just giving them.

3. Don’t make it personal

Instead of saying ‘You’re wrong’, try saying ‘I disagree and here’s why’. People will feel less personally attacked and humiliated and are less likely to be aggressive as a result.

4. Emphasise common ground

This is straight out of the negotiating handbook but it’s essential to find common ground as entry points for introducing difficult messages. For example, in her book The Influential Mind, neuroscientist Tali Sharot describes how doctors in the US had better child vaccination rates when they gave up trying to disprove negative scare stories and emphasised that they shared the same goal as parents – namely the children’s health.

5. Use diffusing phrases

Even if you are struggling to understand someone else’s position it’s important to acknowledge that you have at least heard that they have one. Don’t go over the top but the odd ‘I can see why this is so hard’ or ‘I understand where you are coming from’ can really help to soothe ruffled feathers and keep difficult conversations alive.