I recently did some media training with the second in command at one of the EU institutions. He was a credible and sympathetic interviewee but his content, to be polite, was dry and boring.

When I pointed out that his rather top-down messaging would be substantially improved by the inclusion of some concrete examples and stories he replied: ‘I know. We (the EU) are really bad at this bit’.

When we dug them out with the help of his communication adviser, they turned out to be surprisingly good and showed that he not only had a demonstrable grasp of what was going on at ground level, but that the EU is genuinely making positive change to people’s lives.

We parted ways with the agreement that it was essential that senior people such as himself start mainstreaming the EU’s success stories into their communications as a matter of habit and urgency, especially in the run up to the European Elections where everyone seems to be worried about the possibility of significant populist gains.

But, contrary to the impression given by self-styled ‘Chief Storytellers’ on LinkedIn, good stories don’t just grow on bushes. While some large corporates are already onto this, most companies and public policy institutions don’t prioritise cultivating and harvesting them, meaning they are often an afterthought that some poor junior communications staffer or intern has to beg for from different departments, stakeholders or member organisations. This is then reflected in the number of senior executives and officials who turn up in my training room without anything concrete to talk about.

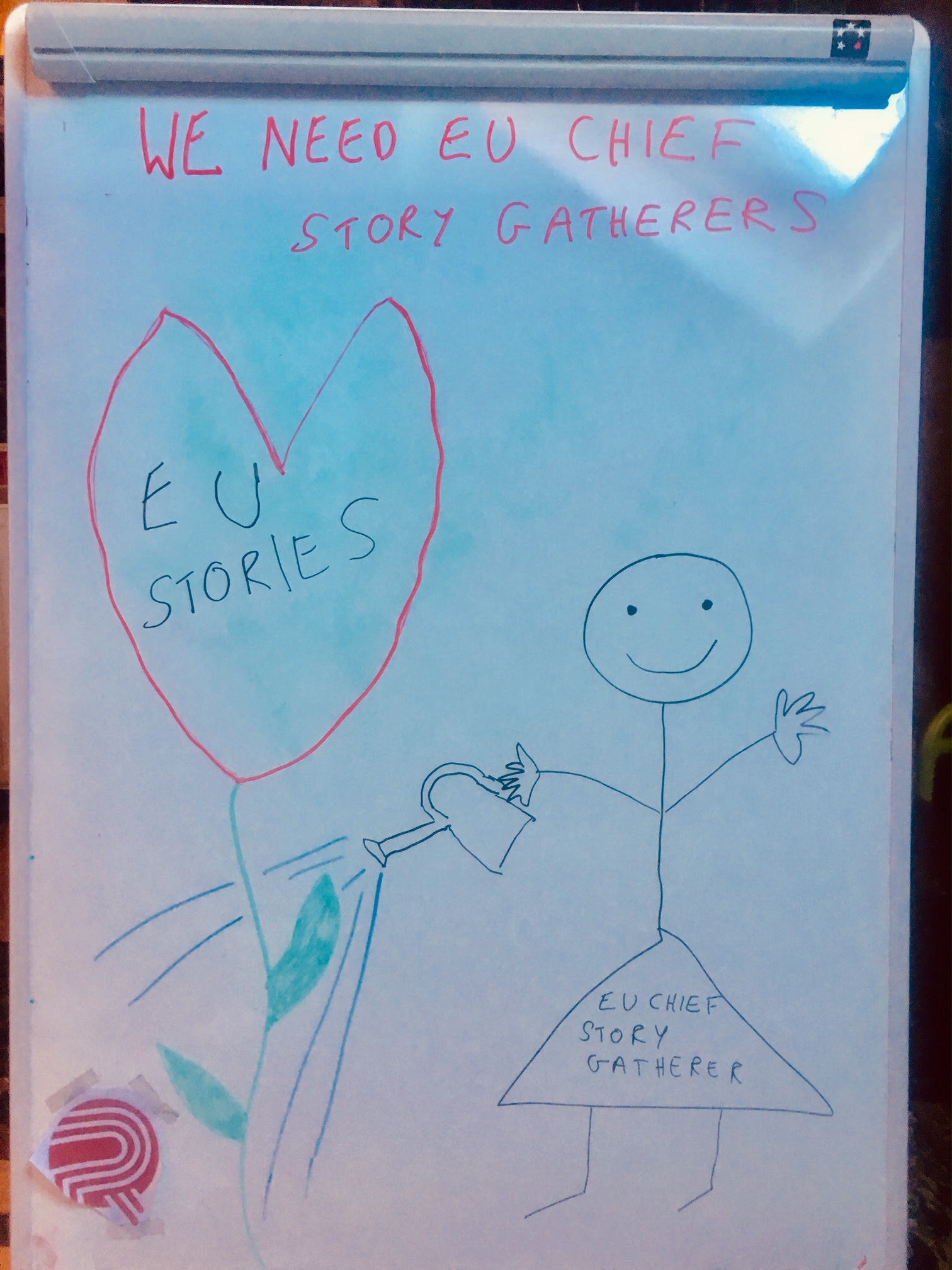

Without buy-in from the top and the allocation of a realistic time frame and resources within which to gather these stories, even the best intentions fail to flourish. I would love to see the creation of a Chief Story Gatherer role for each EU institution or agency (the Commission could even have one per DG). This (senior) person’s job would be to gather the positive impact stories from within their DG (and further afield) and cultivate and frontload them to senior officials for interviews and public speaking events as a priority not a nice to have.

There is no reason why Brussels based non-EU bodies couldn’t do this either. Obviously, it’s a resource issue but it’s an important area and one that’s becoming harder to ignore as we learn more about the neuroscientific impact of stories on empathy, hope and trust. I suspect part of the challenge lies in the word storytelling itself, which is often associated with childishness, frivolity or make believe. Smart people know it’s anything but.

Obviously, a clear brief is important as it will help story-gatherers fend off potential objections – such as commercial sensitivities – from trade association members, or privacy concerns about legal matters. Ways to get around this include anonymity, highlighting pertinent issues rather than individual companies or countries and so forth. Each EU institution, company or body could set their own story gathering criteria. But it would need to be precise so that it’s easier for those who need to supply the information to know what’s relevant.

Of course, there are already good individual examples of positive impact story initiatives from the EU and the kind of work that gets achieved in Brussels. But given the structural problems of communicating Brussels, human beings’ pre-disposed negativity bias, let alone the current challenges the union faces, it’s more essential than ever to show the success stories that give people hope and enthusiasm.