Before you start reading

- This is a post for people who are already using stories as part of their EU policy communications work or are curious about trying them out.

- If you’re not yet at that stage, or still need to persuade colleagues, I have written previously about why soft evidence is important here.

- This is a shortened excerpt from my forthcoming book about how to improve messaging in and around the EU (i.e. the entire Brussels Bubble). For updates straight to your inbox, please sign up below.

Colour makes stories stick

If you’ve been to one of my media or presentation training sessions, you will have heard me talk a lot about ‘colour’.

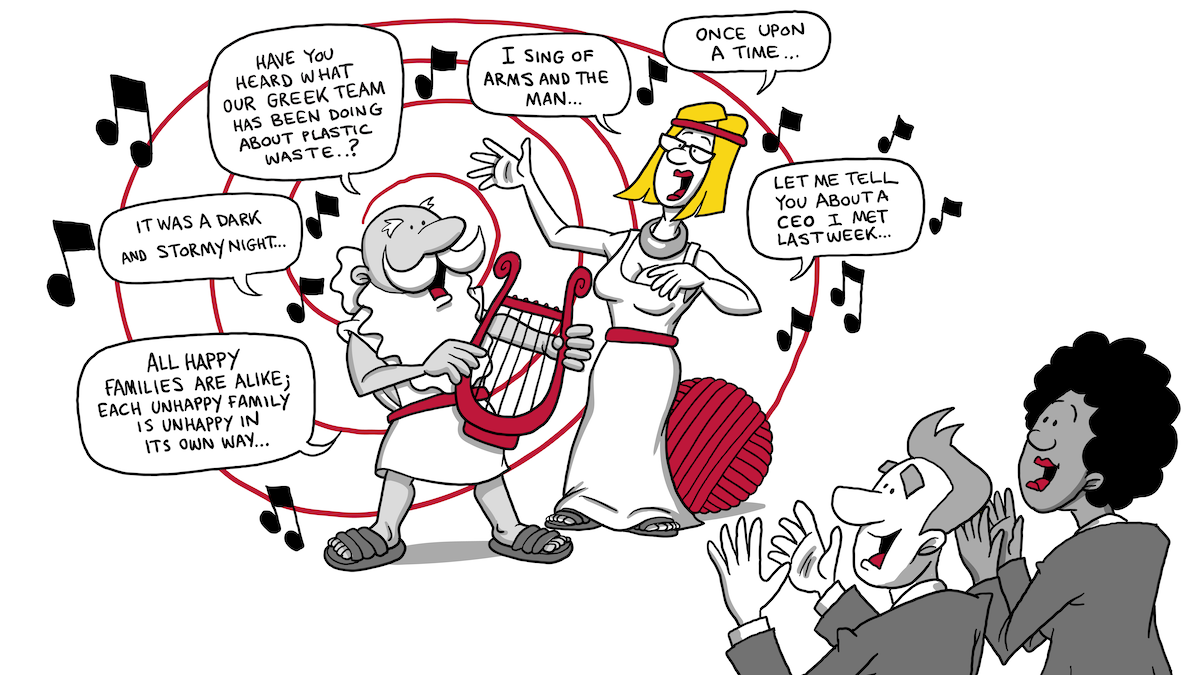

Colour is media trainer jargon for the small vivid details that make a piece of content relatable and memorable. We usually find it in stories, anecdotes, examples or data visualisations. The reason we need colour in communication is that its’s visual and vivid, both of which are Velcro for an audience’s brain.

In other words, the more visual the language and detail the more relatable and memorable it is likely to be. Which can only be a good thing if you want a busy policymaker, journalist or colleague to remember what you said or wrote.

In corporate storytelling, colour is one of the key determinants for whether a piece of content is a genuinely a story or merely a marketing case study. The latter is often written in corporate speak and emphasises processes or buzz words that marketing and sales teams think potential new customers want to hear.

Crucially, it is all too often vague and lacking the vivid detail to make it colourful.

But what do we mean by vivid details and how many do you need to include to be effective?

What counts as vivid detail?

Let’s look at a recent case study from You and Yours, BBC Radio 4’s consumer affairs programme.

In this episode, the presenter is interviewing Rob Jolly, the founder and CEO of electric car rental company, Onto. It’s a long interview in which he talks about his reasons for starting the company at the age of 28, why electric cars are so important, driver concerns and other issues.

The part that stood out as colourful for me was this two-minute excerpt (starts at 08:52) where Rob talks about the company’s early days as a start-up.

Have a listen and see what you pick out.

Three different types of colour

From my perspective there are three obvious categories of details which provide the colour.

- Names: he names his co-founder as Dannan twice. Naming people makes them automatically more real to the audience. It’s pretty hard to imagine someone who doesn’t have a name.

- Small numbers: He refers to the five cars they started the company with. Later he gives specific times of day i.e. taxi drivers who would make a booking at 4am and then ring to complain at 5 am when the car wasn’t ready to pick up because the booking system didn’t work. The crucial point here is that we can almost see Rob and Dannan looking at the clock and imagine their panic at realising a booking hadn’t gone through.

- Visual language: Rob uses a lot of word pictures that help the audience to visualise themselves in the room with him. For example, he talks about ‘washing’ and ‘cleaning the cars’, sorting the badges for the taxi drivers etc. Can you imagine if he had talked about ‘optimising the fleet’ instead? It wouldn’t have been nearly as sticky.

Crucially, Rob struck the balance between providing enough detail for the story to stick but not so much that it would have been hard for the brain to absorb.

Vivid details help us empathise

Unsurprisingly, if vivid detail is relatable and memorable, it offers the secondary possibility of helping an audience to empathise.

In Rob’s case, his deliberate choice of down to earth, colloquial language helps the audience relate to him. He describes the early days as ‘scrappy’ and ‘unglamorous’ both of which pack a punch emotionally.

By using language and detail that everyone can relate to, he provides a snapshot of controlled vulnerability. Being able to show vulnerability is crucial if you want to communicate credibly about a challenging topic.

And yes, I’m talking to anyone with a net zero plan, or any other equally challenging issue. To be credible, you will need to talk about the really hard stuff and one of the best ways you can do that is with carefully prepared, examples that offer the right amount of colour and vulnerability.

Next steps for policy communicators

- Be on the lookout for different types of colour and consciously build it into your policy communications, especially your speaking events.

- Add qualitative questions to quantitative surveys/research etc.

- If you are sourcing case studies from colleagues, or a wider network, ask for specific details such as times, names and concrete actions. If you ask vague questions, you will get vague answers. And the opposite of vague, in case we needed reminding, is vivid.

- Get permission to use these details up front, so that you don’t have to go back and forth on the approvals process.